It behaved the Carmelite Father, to introduce the great Marian figure, the blessed Marie de l’Incarnation.

Baptised on a 2 February, at that time feast day of the Purification of the Virgin Mary, yet consecrated to the Virgin Mary since before her birth, the one who said, “that it is good to die daughter of the Virgin, that it is good to die a Carmelite,” left this earth on an 18 April, while the convent’s bell tower rung the Regina caeli.

Her entire life unfolded under the sign of the Virgin Mary, as much as by the worship that she dedicated to Mary (prayers, pilgrimages, and so on) as by the Marian graces that she received, Our Virgin Lady having often visited her.

Indeed, we are able to testify, like Mother Jeanne de Jésus Séguier: “That blessed was given by God to this holy Order of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, reformed by Saint Teresa, for the happiness and blessing of this Order in France.”

MADAME ACARIE, DISCIPLE OF THE VIRGIN MARY

By father Jean-Gabriel RUEG, ocd (Toulouse)

Preliminary remarks. In this year marking the fourth centenary of the establishment of the Teresian Carmelite Order in France, it is important to highlight the place of the Blessed Virgin in the heart and spirituality of the person who inspired, one could go so far as to say founded, the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel in our own country. My talk will have two main parts. I shall begin by giving an outline of the central place occupied by the person of Mary within the Carmelite Order, in that she is a model of faith and love for every Carmelite. Secondly, having made full use of all the available depositions relating to Blessed Mary’s life, I shall endeavour to sketch a Marian portrait of the person who was known as Madame Acarie before becoming Sister Mary of the Incarnation in the Carmelite Order, having contributed so greatly by her own efforts to the establishment of the Order in France; for it is a fact that, as André Duval wrote, “Under Mary’s guidance [this is how he referred to Madame Acarie], and through her initiative…God brought the religious Sisters of the Blessed Virgin, founded by Blesses Teresa and styled ‘of Mount Carmel’ to the Kingdom of France and, with her as intermediary, [He] distributed the said religious throughout every part of the kingdom.” We shall discover the ways in which Blessed Mary was indebted to her Holy Patroness for all the graces that bore fruit, through her efforts, in serving the mission of the Order.

Mary in Carmel

It is above all by its fundamental identity as a school of Marian holiness that the Carmelite Order seeks an understanding of its devotion to the Mother of God. Devotion to Mary serves no good purpose unless one endeavours with all one’s might to imitate the Virgin of the Annunciation (a mystery to which numerous Carmelite houses are dedicated, along with the mystery of the Incarnation); for Mary’s entire existence was nothing but a continual ‘yes’, an acceptance of the will of God in her regard. Such a devotion to Mary involves a radical consecration, following the example of the one who offered herself completely to the will of the Father and who invites us to surrender ourselves in our turn, in a gesture of love and confident self-abandonment.

The Blessed Virgin is Mother of Carmel in the measure that she gives birth to sons and daughters who will imitate her in carrying out that “living sacrifice, holy and tooltip}acceptable to God” {{end-text}Romans, Ch. 12, v.1 (NRSV translation). {end-tooltip}of which St. Paul speaks, that “spiritual worship” which consists in “presenting oneself” to the Father’s love. The Blessed Virgin must not remain a remote and inaccessible figure within the Carmelite Order, quite the opposite; to contemplate Mary and to imitate her is to respond to the Carmelite vocation in its quest for union with Christ in Pure Love, and for spiritual fruitfulness for the salvation of mankind. St Thérèse of the Child Jesus understood this quite clearly when, at the end of her short life, she said to her sisters that one must not make the Blessed Virgin someone “unapproachable” as was the tendency at the time, but someone “imitable”“They show her to us as unapproachable, but they should present her to us as imitable.” (Last conversations: the Yellow Notebook, Aug. 21. Washington: ICS, 1977).. What is more, the Second Vatican Council asks us to contemplate and imitate the one who “in her life…has been a model of that motherly love with which all who join in the Church’s apostolic mission for the regeneration of mankind should be animated.” Ch. 8, para. 65.

The mystical life that is at the heart of Carmelite life is a life moved by the Holy Spirit. To live in the shadow of the Holy Spirit is to be like Mary, who received the odumbracion (overshadowing) of the Holy Spirit, to use the well-known expression of St. John of the Cross “The Angel Gabriel called the conception of the Son of God…an overshadowing of the Holy Spirit.” (The Living Flame, stanza 3, para. 12, in Collected works of St. John of the Cross, rev.ed., tr. K.Kavanaugh and O. Rodriguez: Washington: ICS, 1991) and, like her, to live in the loving faith that gives birth to the Saviour. For, as St. Ambrose wrote, “Every believer conceives and gives birth to the Word of God according to faith”, an idea that re-occurs in the document Lumen Gentium “The Church, by receiving the Word of God in faith, becomes herself a mother.” (Lumen gentium, Ch. 8, para. 64).and is confirmed by Blessed Titus Brandsma : “The goal of our Marian life should consist in becoming in some way another Mother of God, so that God may be conceived in us and born of us.”

It is as a consequence of having fully accepted the gift of God, the “Living Flame” within her, and of having responded to His call by surrendering herself completely to His transforming action, that Mary can be considered as the perfect model not only for the Carmelite but also for every Christian.

Mary, Formator of the spiritual life and model of faith

Mary is honoured in Carmel not so much by marks of exterior devotion as by a genuine interior devotion that considers her as the great spiritual formator of Carmelite men and women, for Mary has gone ahead of them on the road of authentic spiritual life. Their filial devotion to their Mother has no other purpose than to enable them to grow in the likeness of Christ. Everything about this devotion, I might add, is summarised in the liturgical prayer for the Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel : “May the prayers of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother and Queen of Carmel, protect us and bring us to your Holy Mountain, Christ Our Lord.”Carmelite Missal (Oxford: Carmelite Priory, 1997)..

Filial dependence on Mary has no other purpose than to unite us more intimately with Christ, the Bridegroom of the soul. A “Mariform” life is always a “Christoform” one, for no creature on earth has ever been or will ever be as closely united to Jesus as Mary was and will be for all eternity. This was the great insight of True Devotion to Mary in Carmel. To let ourselves be taught by her is to share in her self-offering to the Love of her Son; it is truly to enter into the mystical relationship that Jesus desires to have with every human being whom He has saved by His Blood, in the knowledge that the Blessed Virgin’s whole-hearted acceptance of the designs of Her Son Our Redeemer was outstanding and that she, more than any other, enables us to accept them wholeheartedly in our turn.

Mary is the best of all possible guides, the best person to form us in our baptismal vocation and call to holiness. She is the “mould” “The beautiful mould of Mary, where Jesus was naturally and divinely formed.” (Treatise on true devotion to the Blessed Virgin, London: Burns Oates, 1937, p. 128). of Christ, to use St. Louis Grignon de Montfort’s expression, who forms Him within us, because it was She who was receptive to grace at the deepest level.

Father Francis of St. Mary wrote as follows :

“… St. John said these poignant words, and the tragedy is ongoing : His own received Him not. Only the Immaculate Conception, freed from the least tendency to self-satisfaction, a true “capacity for God,” was able to receive the gift of God in its totality and at every moment. The fiat that she uttered on the day of the Annunciation was none other than the visible sign of the continual disposition of her soul.”

“The continual disposition of her soul” reminds us of St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus and her declaration in the infirmary to her sister Mother Agnes, a declaration that many followers of St. Thérèse consider to be the essence of her “little way” :

“Holiness is not a matter of any one particular method of spirituality; it is a disposition of the heart that makes us small and humble within the arms of God, aware of our weakness but almost rashly confident in His Fatherly goodness.”Beevers, John; Saint Thérèse, the Little Flower: the making of a saint. Rockford; Tan Books, 1976, p. 138.

Yes, this is what is absolutely extraordinary; we can only offer God our nothingness, our nothingness as the capacity to receive God’s love for us. In Paul Claudel’s masterpiece, The satin slipper, there is a really wonderful observation on this subject.

Don Camillo, who was antagonistic towards the mystery of the Incarnation and who did not believe that God descended into Mary’s womb, a woman’s womb, asked Doña Prohèze : “So ‘twas nothingness that God desired in the woman’s lap ?”

She gave the astonishing reply “What else did He lack ?”The satin slipper : London; Sheed and Ward, 1931. Third day, Scene 10.

Yes, indeed, what does God lack? Nothing, for sure; He is all-powerful, He is infinite and infinitely perfect! What can He possibly lack but our own nothingness, something that appears to Him as capacity, receptivity, space, into which He can pour out His love. This profound intuition is the main factor in the spiritual doctrine of Thérèse, who wrote, “It is necessary that…it lower itself into nothingness and transform this nothingness into fire.”Story of a soul, tr. J. Clarke; Washington: ICS, 1976, p. 195. What God expects of us, what He has need of, so to speak, is for us to offer Him our nothingness as mortal and sinful human beings, so that He can express His need to give Himself, to pour Himself out; “You would be happy not to hold back the waves of infinite tenderness within You,” as St. Thérèse wroteIbid., p. 181. in her Act of Offering to Merciful Love on June 9, 1895.

Mary teaches us, as she taught her little sister Thérèse, that Christian life and holiness are not a question of amassing good works and of tasks to be accomplished, but of opening ourselves completely and consenting at the deepest level to the work of grace within us, of offering our nothingness to the action of Merciful Love. “The weaker one is, without desires or virtues, the more suited one is for the workings of this consuming and transforming Love,”, wrote Thérèse to Sister Marie of the Sacred Heart.Letters of St. Thérèse, Vol. 2, 1890 –1897, tr. J. Clarke: Washington:ICS, 2002. Letter of Sept. 17, 1896.

This is the fundamental attitude put before us by the Little White Flower of Lisieux, who wished to be schooled by Mary in the way of spiritual childhood and to sing unceasingly of the mercies of the Lord.

Like Mary, Thérèse to live out the acceptance of God’s gift, the gift of grace aimed at making us righteous and holy, not by reason of our own works and merits (St. Paul says we have nothing to boast about in this respect), but solely because of Christ’s mercy and the merits of His Passion and glorious Resurrection. What God expects is that we consent with the whole of our being, in a spirit of total interior poverty and confidence to the point of audacity in His goodness as a Father, to our rebirth in the Holy Spirit, that we allow ourselves to be consumed by this fire of love that “Transforms everything into Itself,” that we consent in faith to our self-offering to Merciful Love, to the point of sharing in the Cross of Jesus. “For love is giving all – is giving self,” said Thérèse.“Why I love you, Mary,” v. 22. (Poems of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, tr. Alan Bancroft: London: Harper-Collins, !996). In saying “yes” to the birth of the Divine Word through the action of the Holy Spirit in her womb, Mary put her whole being, body and soul, at God’s disposal. The gift of faith implies the gift of oneself…unto death, death on a cross. We can imitate Mary in her attitude of faith. She is a model of faith, of trust in God and of obedience to Him, in spite of the aridity and darkness experienced along the way.

The deepest secrets of the Kingdom are revealed to little ones. (See Matthew, Ch. 11, vv. 25 – 27). To Mary, the little one, was revealed the secret of the Father, His Incarnate Word. Because she said yes in daughterly obedience, Mary experienced the fullness of union with the will of God and His presence; and Mary is the Mother of the Church. In other words, it is she who calls on each one of us to accept the Divine Life and to make it fruitful by our cooperation with Christ for the salvation of souls. “To be a Carmelite, and by my union with You to be the mother of souls,” tr. J. Clarke: Washington: ICS, 1976, p. 192. said Thérèse. Like Mary herself, through faith and in the communion of saints, the Christian brings to birth new members of Christ’s Body.

Every Christian is called to imitate Mary’s “Yes.” Hans Urs von Balthasar was very much to the point whenhe wrote, “The one fundamental act can be accentuated in many ways, and, in this sense, leaves room for many spiritualities, but they all proceed from the same centre and must also go back to it – to the one Yes of Christ, of Mary and of ecclesial man to the saving design of the Father for all and each. But it is the Holy Spirit who effects the unity between the Father’s disposition and the answering Yes.”Ratzinger, Joseph and Balthasar, Hans Urs von. Mary, the Church at the source; San Francisco: Ignatius P., 1997, p. 121.

For all the great mystics of Carmel and especially for St. John of the Cross (although he only mentions her seven times in the whole of his writings), the Blessed Virgin is the embodiment par excellence of the bride-soul united to God and transformed into Him. (It is for this reason that Titus Brandsma considers St. John of the Cross to be a “Marian mystic”). It is in consequence possible to understand why the Carmelite Order recognizes itself at the deepest level in the mystery of Mary, and why it can be termed “all Marian” (totus Carmelus marianus est). There is no doubt that the men and women who have donned her habit (“Our Lady’s habit,” St. Teresa calls it, in the Prologue to the Book of the Foundations), have clothed themselves in the maternal protection of their Heavenly Mother, but there is still more, for from the time of Elijah the garment bequeathed to them has represented the spiritual portion bequeathed to his disciples (the “double portion of his spirit”), the prophetic and mystical heritage of the Mother of the Redeemer, she who in the obscurity of faith, in silence and in solitude, in the humble acquiescence of a life surrendered to the action of grace, in the martyrdom of a loving heart, gave birth to the Saviour of the world. This is the plan of co-redemption that Carmel is called upon to embrace, if it wishes to be faithful to that portion of the heritage bequeathed to it by its Mother.

Madame Acarie and the Blessed Virgin

Madame Acarie remained firmly committed to the Marian vocation of the contemplative Order of Carmel. As we shall see in the second part of this talk, the woman who was the inspiration behind the Teresian Carmel in France received from her earliest years the profound imprint of a Marian seal that would never be effaced with the passage of time. As a tiny baby, Barbe Avrillot had already been dedicated to the Blessed Virgin by her parents.

“Our Blessed Sister Mary of the Incarnation was brought into the world by illustrious parents, in a legitimate union, on the first day of February, and was baptised on the day of the feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin, as she told me on several occasions.

Her father, Nicholas AVRILLOT and her mother, Marie LHUILLIER, members of the most illustrious families in Paris, were very pious and devout Catholics who had a great devotion to the Blessed Virgin and so, seeing that they were unable to rear any children…several of them having died at birth…when her mother was expecting her, they made a vow to dress her in white until she was seven years old, in honour of the Blessed Virgin.”Most of the quotations referring to the “sayings or deeds” of Blessed Mary are taken from the Beatification Process.

And the vow was put into effect, for the future Blessed Mary would, from the day of her birth until the age of seven, wear white garments as a sign of her consecration to Mary, garments “made of a fabric in common use amongst the lower classes,” adds Mother Marie of the Blessed Sacrament (Saint Leu).

Very early on, then, we see the future Blessed Mary signed with the seal of the One to whom Barbe Avrillot would not long after promise unceasing and undivided honour. Under the direction of one of her aunts, a nun in the Order of St. Clare in the monastery at Longchamp, where little Barbe was a boarder from her seventh to her twelfth year, she began, says Mother Frances of Jesus, who was one of the sisters with her in the Carmel of Amiens, “to taste the spirit of devotion, to serve the Blessed Virgin and to meditate on the decades of the Rosary, by which means she received great graces; she continued this devotion for the rest of her life, as we observed in the convent during her time here.” She would remain faithful throughout her life to the daily recitation of the Rosary, in spite of the difficulty she experienced in praying vocally. Because of her fidelity, she was sometimes obliged to say it late at night, if her duties had not allowed her the opportunity to do so during the day. She would even get someone to say it with her so that she would be able to finish it.

She had, we are told, a very special confidence in the intercession of the Blessed Virgin, whom she considered as “her usual refuge in every circumstance.” So, before beginning any action “we used to see her kneel down and say a Hail Mary.” She generally advised them, before beginning mental prayer, to make a practice of either invoking the Holy Spirit, as is the custom in all Carmels, or saying a Hail Mary.

Before entering the strict enclosure of the Carmelite Order, newly established in France, Barbe was, however, a mother who took care to train her children in the same practice of devotion to Mary, as her eldest daughter records in her deposition :

“As for the shrines dedicated to the Most Blessed Virgin, she would often visit these on foot; she went to the underground chapel of Notre Dame de Bonne Nouvelle in the Abbey of St. Victor, to the churches of Notre Dame de Lorette and Notre Dame des Vertus, also on foot from time to time; the handicap resulting from her leg would not allow her to do this on all the occasions when she was moved by devotion to go there, and she would go in a carriage. She went twice to Notre Dame de Liesse; I don’t know if she went there more often, but I had the honour of accompanying her to all the places I have mentioned. She also went out of devotion to Notre Dame de Chartres and, I think, to Notre Dame de Saumur, but I am not quite sure of this.

On all the feasts of the Blessed Virgin we would visit the church of Notre Dame in Paris. She fasted in her honour on all the vigils and Saturdays of the year, from Christmas to the Purification, even on those days when Holy Church allows us to eat meat. She encouraged all the members of her family to have a devotion to the Most Holy Mother of God and to have recourse to her.”

In Carmel, she would substitute for these pilgrimages visits to the hermitages. During the seventeen months when she was in the Carmel in Pontoise, she had a room in the house turned into a hermitage and another hermitage built in the garden. Both were dedicated to the Blessed Virgin and she would visit them every day if she could, in spite of her infirmities and her potences!

Nevertheless, this devotion to Mary remained, as it should, very Christocentric. The witnessed testify that she never separated the Holy Mother of God from her Son Jesus. Praying the Rosary, I might add, enables us to meditate with the Blessed Virgin on the entire life of Our Lord. The witnesses also saw her, during her frequent bouts of illness, “absorbed in such loving prayers addressed to Our Lord and to the Blessed Virgin that we were all enraptured.” “She began to say such wonderful things about the merits of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the Most Holy Virgin, adding most fervent prayers for Holy Church, giving proof during her grave illness of the great desire she had for the glory of God and the extension of His Church.” She remembered, they said, how St. Bernard explained the heavenly intercession of Christ and His Mother : “The Mother shows her Son Jesus Christ that she has fed Him with her own milk; the Son in His turn showsHis wounds and His blood to His Father; and by bringing all this into the sight of God, it is impossible for us not to obtain the confirmation of our petitions.”

A few days after she entered the Carmel of Amiens as a lay-sister, in 1614, she wrote the following words to her friend the Marquise de Maignelay, words full of thanksgiving to Christ and His Mother :

“ I am here [in religious life] with regret at seeing myself so feeble and lacking in virtue; but I am greatly indebted to God for He has given me these few days to begin thanking Our Lord Jesus Christ and His Holy Mother for such a great mercy.” Seven weeks later she received Our Lady’s habit and the name Mary of the Incarnation that she had been given “in a heavenly revelation, on account of the devotion and love she felt for this most holy mystery, the summit and source of our Redemption.”

To a white-veiled sister, who asked her later on why she had changed the name of a saint who was so highly revered at the time, she replied, “with a smile, I’m quite sure that Saint Barbe won’t be put out by my taking the name of the Blessed Virgin.”

Her gratitude to and love for the Mother of God did not diminish in Carmel, quite the reverse. The habit in which she had been clothed was for her a sign of the protection of the Queen of Carmel. “She would often kiss her scapular out of reverence, saying, Oh, what a mercy it is to wear the holy habit of the Virgin; oh, how unworthy I am to do so,which greatly edified…all the sisters, for she inspired them by her words to reverence their vocation and give thanks for it.”

When she fell ill in Amiens, before her profession, she kept her eyes fixed on the portrait of the Virgin that she had asked to be brought to her, saying, “from time to time some wonderful things regarding the excellence of the Most Holy Mother of God and of our happiness in having her as Mother of the Order…She added this observation, which greatly edified us : Our Mother Saint Teresa said on her deathbed that it is good to die a daughter of the Church; as for myself, I say that it is good to die a daughter of the Blessed Virgin; it is good to die a Carmelite.”

Her life with Mary

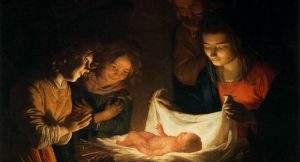

In his deposition for the Ordinary process, Michel de Marillac vouched for the authenticity of the apparition of the Virgin and Child to Mary of the Incarnation and for the “effect of recollection and reverence” it had on her. It took place in Pontoise Carmel, ten days before her death on Palm Sunday, 1618. It was the occasion of his last visit to Mary, with whom he had formed a deep spiritual friendship.

The Virgin and Child : here we have the perfect symbol, as it were, of our Blessed Carmelite’s spiritual outlook, for her extraordinary humility (her chief attribute) brought her into such close conformity with her two models.

She was accustomed to saying to her sisters, with reference to the Infant Jesus, “he made Himself little, to teach us to become little ourselves. When shall we become little?” Sister Marie of the Blessed Sacrament confirms this observation when she says that the Blessed Carmelite had a great love for the Holy Childhood of Jesus and “of seeing Him as a tiny baby in the crib…At Christmas, according to our custom, we would make a model (of the crib) which was kept in place for six weeks. Every day, Blessed Mary would spend a long time in front of it. Sometimes she would remain motionless and oblivious of her surroundings. Sometimes they would give her Baby Jesus to hold in her arms. She would caress Him with such gentle, innocent tears and sighs that when you looked at her it seemed as if she had been entirely transformed into that Divine Littleness. Sometimes, wearing a joyful expression as if she wanted to entertain the Infant Jesus, she would burn sweet-smelling pastilles in His presence.

On the holy Feast of Christmas, it seemed as if she was unable to contain herself and as if she wished to fill the whole earth with joy and exultation. She would say wonderful things about the Divine Mystery and her fervent discourses would set her sisters’ hearts on fire. It was quite evident that her love for the Infant God made her oblivious to herself and to everything else, for she usually took extreme care that there should be no visible signs of the great things God communicated to her spirit.”

Her love for the Divine Infant was not confined to mere devotion. In conjunction with her love for the Blessed Virgin, it enabled the future Blessed Mary to follow the path of humility, the path taken by Jesus and His loving Mother. So her everyday duties were accomplished in imitation of Jesus Christ in His hidden life, as Sister Jeanne of Jesus says in her deposition :

“She would say wonderful things to me about the holy and humble actions performed by the Son of God on earth, particularly during the thirty years when all that is said of Him is that he was subject to the Blessed Virgin and to St. Joseph.”

But above all, the humility of God the Son made Man produced within her, long before Thérèse of the Child Jesus, the childlike spirit so characteristic of the Carmelite of Lisieux and of the fundamental approach of the Teresian Carmel that we attempted to define in the first part of this talk.

“She said the following; God allows a soul to suffer frequent falls because we arelooking to obtain too much strength and support from ourselves. If we were to leaveourselves behind and expect to obtain all our strength from God, then He would notlet us fall so often. She said that humility was the spirit of truth that allowed us to see the truth of who we are, in our poverty and nothingness. She said that we should no more be astonished to see imperfections in ourselves than to see a dung-heap in a stable, for that where it belongs; but what should give us more cause for astonishment is to see virtues within ourselves, all the more so because they come, not from ourselves, but from God.”

This deposition, with its echoes of St. Thérèse, helps us to understand more clearly that the “little way” epitomised by Thérèse of Lisieux and transmitted to the world through The story of a soul is the fundamental attitude of the Carmelite soul. Did not Mary of the Incarnation say, referring to the practice of humility or littleness in the spiritual life, that she cherished the souls who took this path to God, since it is the shortest and the most secure? Do we not seem to hear Thérèse speaking to us already about the “short cut of her little way”? It involves awareness of our need but at the same time confidence in the One Who can raise us up, as demonstrated in the following quotation, which again is so reminiscent of Thérèse :

“We must never lose heart. What are we, when left to ourselves, for heaven’s sake? Do you think there could be anything good in us if it were not put there by God? We must be very much at peace in seeing ourselves as we are. We must act like a little child does, when he falls down in the street and spoils his clothes. Even if he sees several other people, he will only go to his mother and throw herself into her arms, although he fully expects to be punished. So we ourselves, at every moment and in every circumstance, must always throw ourselves into the arms of God, our Good Father, and abandon ourselves to His mercy.”

But for a more detailed study of this aspect of the spiritual relationship between the Foundress of Carmel in France and the new Doctor of the Teresian Carmel, you would do well to consult the splendid work by Monsieur Bonnichon : Madame Acarie : une petite voie a l’aube d’un grand siècle. (Eds. du Carmel).

Conclusion

We are only too aware that we have merely touched on some outstanding features of the spiritual life of the woman who has been described as “given by God, through the Blessed Virgin’s intercession, for the wellbeing and benediction of the Carmelite Order in France.”

We wish simply to emphasise the central place occupied by the Blessed Virgin in the whole Carmelite Order, in that the Mother of God not only gives us her maternal support but is also a model of faith, confidence, humility and self-giving for every Carmelite. This was already Madame Acarie’s experience “in the world” before living it fully by being clothed in Our Lady’s habit, in the Order that, thanks to her determined efforts, would become so widespread in our native land. The fourth centenary ought to be an occasion to honour her on this account.

Most quotes from “facts or facts” of the Blessed are taken from her process of Beatification.