Mary of the Incarnation’s attitude to Sacred Scripture has made her a mistress of the spiritual life in the tradition of the Reformed Carmelite Order.

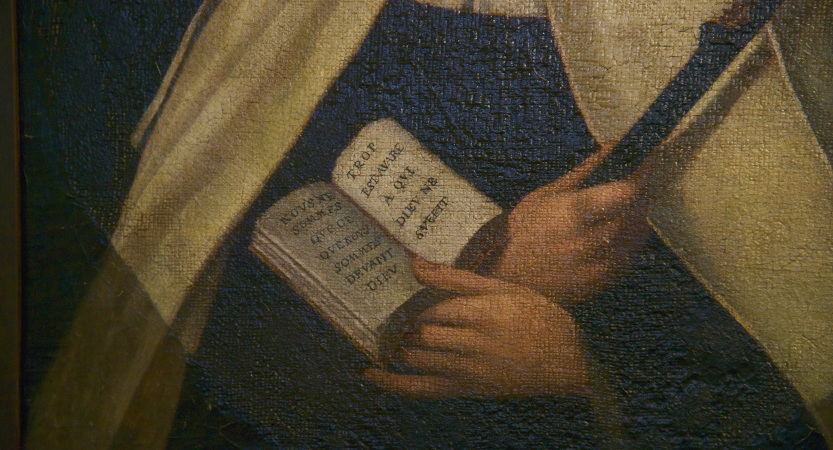

Blessed Mary was herself consoled, and consoled others, through her assiduous reading of Scripture, a reading that conditioned her to a life attuned to the Word of God : “She always carried the Holy Gospels with her, and would write out passages on scraps of paper and give them to us when we went to see her.” See the example, below, in her own handwriting, a slip of paper which reads, “St. John, Ch. 6: Do not work for food that cannot last, but work for food that endures to eternal life, the kind of food that the Son of Man is offering you.”

Mary of the Incarnation and the Holy Scripture.

Published in Avenir du Carmel, No. 30, Winter 2001 (Paris Province) pp 5-13.

Based on the lecture by Frere Marc Fortin (Priory of Lille) in Pontoise Carmel, October 7, 2001

Madame Acarie is an attractive representative of spiritual life as it was lived at the dawn of the « Splendid Century ». She gave the Carmelite Order to France before becoming herself a gift to Carmel. I should like in this lecture to give an overview of the extent to which she lived out one of the fundamental principles of the primitive Carmelite Rule, « To meditate day and night on the Law of the Lord ». This re-use of the first of the one hundred and fifty psalms by the Patriarch of Jerusalem is traditionally taken to be an injunction made to the first hermits that they should stay awake, listening to the Word of God. In the Carmelite Order of today, it is as usual to read the Word of God as to listen to it. This feature of Christian life may have become familiar to Catholics in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, but it would be less familiar to a nun reaching spiritual maturity at the height of the Counter-Reformation. But the question is worth asking : in what way did Mary of the Incarnation read Holy Scripture? The reply will enable us to discover a woman who is closer to ourselves than we would have expected. I hope, in this study, to help you to become acquainted with that person.

It is true that an enquirer can be put off by the number of documents that are available. The variety of these must not conceal one major difficulty, that is, the testimonies of third parties appeared in great numbers after her death, at a time when writings in her own hand remained few in number. They were mainly collected together in the Book of the Constitutions, which Blessed Mary kept with care. In addition to her Act of Profession, Mary of the Incarnation copied into the book, or had copied for her, some texts relating to the mystery of Christ, to which she had dedicated her life : the Prologue of the Fourth Gospel, the Church’s Profession of Faith, extracts from the Roman Liturgy, (the Prefaces from the Masses of the Nativity and the Holy Trinity), Liturgical prayers (the Veni Sancte Spiritus and the Gloria) or para-liturgical ones (Litanies of the Holy Name of Jesus), to which were added some maxims of St. John of the Cross. In her tiny writing, the whole of this occupies the blank spaces in a small volume which has been carefully bound in leather. Texts from the liturgy are to be found in some pages which have been typed in. the uniform use of Latin serves only to accentuate the French of the maxims of the Spanish master. Some more relevant texts, of which we do not always possess the originals, complete this archival deposit. They consist of letters and a collection of spiritual counsels which throw greater light on her spiritual life. These were in fact published after her death. They appertain to the biographical and hagiographical research devoted to the memory of the Pontoise Carmelite, beginning with André Duval, who made use of some of her letters in 1621, and continuing to her most recent biographer, Father Bruno of Jesus and Mary, who was able to take advantage of the discovery of the collection Les vrais exercices in the Bibliothèque Nationale between the wars. From the time of Duval to Père Bruno, other writers of the lives of saints have drawn on other discoveries. The fragmentary nature of the documentary collection is unfortunately of no help to the present-day reader’s understanding. To make progress, he has to devote himself patiently to a laborious course of reading, for there are libraries and Carmelite archives which hold deposits of testimonies which have as yet scarcely been exploited. The testimonies were produced by individuals who were close to her. Her confessor as well as her Carmelite Sisters (or other relatives) have left striking descriptions of her. The most outstanding features of her temperament or her physical appearance which they describe help us to realise all the more clearly the perceptiveness of her sayings. Collected in biographies or in the proceedings of the various processes relating to her beatification, they await the twentieth-century men and women who wish to profit from this living embodiment of ancient Carmelite teaching.

But the abundance of manuscripts and printed works renders the task a difficult one : this is compounded because the spontaneity of the source material can prove to be a formidable obstacle; the language of the seventeenth century is not the language of today, that is for sure, even without taking into account the fact that the best dictionaries cannot throw light on the religious consciousness of another era. With the best will in the world, a Christian can have the feeling of being all at sea; having begun by encountering the scrupulous reticence of a Carmelite nun, he is now left open-mouthed by passages of florid prose. Where is the truth to be found? Surely only after a period of solid work, in the humble acknowledgement of the gulf created by the centuries.

A reading of the Papal Brief confirming Mary of the Incarnation’s beatification will assist the intrepid researcher. As an introduction to the text, Pope Pius VI gives concrete expression to an important Biblical idea which runs throughout the Old and New Testament. It is the idea of « consolation ». This is what he writes :

« Blessed be the God and Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of all mercies and the God of all consolation, who consoles us in all our trials and in the multitude of labours which overwhelm us at the present time, a time which is full of difficulties for the Catholic religion, so that [this religion] may be kept pure and spotless, in spite of the scandalous innovations and schisms which men who are enemies of all religion have recently instigated as opponents of the Church in France, that Kingdom which was so flourishing in former times. The God of goodness increasingly brings forth consolations for us, in the very place from which our heaviest crosses arise, because in the heroic virtues of the Servant of God, MARY OF THE INCARNATION, lay-sister and foundress in France of the order of nuns known as Discalced, of the B(lessed) V(irgin) Mary of Mount Carmel. He causes us to find an abundant source of spiritual consolation. [An account of her life follows] since the whole conduct of her life and actions is an only too visible condemnation of all the innovations arising in France in our day it seems that it is only through a particular providential act of God, that after almost two complete centuries, has been reserved to the times in which we live, for our consolation and the support and sustenance of her fellow-citizens, and for the honour and adornment of the Catholic Church, the possibility of requesting the veneration of the peoples for this Servant of God, and of having homage given to her … [Given at St. Peter’s in Rome, under the seal of the Fisherman’s Ring, May 24, 1791] ».

When he wrote these lines, Pope Pius VI was a man weighed down by problems. The philosophers of the Enlightenment and the eighteenth-century rulers of Europe dealt harshly with the institutional Church. Their forces were directed towards the destruction of one of the visible forms of Christian life, that is, life consecrated by public vows. The damage caused by the France revolutionaries awakened painful memories for the Holy Father. At the time when the Carmelites of the Hapsburg Empire were thrown out onto the street and given shelter by their sisters in France, he had received a letter from Teresa of St. Augustine, who was a finally professed Sister in the Carmel of Saint Denis and daughter of Louis XV. These are the opening lines :

« Most Holy Father, the storm which has devastated one part of Carmel has laid waste to all the others, and all the Holy Mountain is covered in mourning, mourning of the saddest kind. In the midst of our tears, the certitude that you share our affliction consoles and sustains us; but this consolation, most Holy Father, would become infinitely more apparent to us, if at the present time it would please you to grant us the favour which we have been requesting for more than a century, and that the whole of France has requested and continues to request along with ourselves, that is, the canonisation of our V(enerable) S(ister) Mary of the Incarnation. She is the Teresa of France. It is she who requested that our Spanish Mothers should make foundations in France, and it is by means of France that God has been pleased to extend our Holy Order to those countries where the storm which now afflicts us had its origin (…) [From the Carmel of Jesus and Mary in Saint Denis, November 18, 1782] »

A month later, on Christmas Day, the Pope replied :

« The affliction in which We see you plunged during these present circumstances, is Our own as much as it is yours, and Our paternal heart is filled with it. What can We desire more ardently than to discover some great consolation which we can share? Such would certainly be, O(ur) V(ery) D(ear) D(aughter) in Jesus Christ, that which your admirable piety has suggested that you should propose to Us as the object of your wishes and those of your sisters; it is that the venerable Servant of God, Mary of the Incarnation, foundress of the discalced Carmelites in France, and whom in consequence you call your first mother in succession to St. Teresa, should be placed by the Holy See in the number of the Blessed and proposed for the public veneration of the faithful (…) For Our part, We supplicate the Author of all good to bestow on you a full measure of His heavenly consolations … [Given in Rome, etc, on December 25, 1782, in the eighth year of Our pontificate] ».

This exchange of letters is therefore the origin of the theme of « consolation » which opens the Papal Brief of 1791. The influence of the Carmelite of Saint Denis is obvious. Even though the Pope does not repeat the expression « Teresa of France » the circumstances of 1791 have made him aware of the connection made by Madame Louise between Blessed Mary and her native land. Moreover, Mary of the Incarnation would be the exception from her country during his pontificate. Pope Pius VI did not beatify or canonise any Frenchmen, nor would he put forward any female models of holiness from amongst the saintly figures of the Splendid Century. It was through the life of a woman, then, that Pope Pius VI called down upon France the consolations which would fortify that country. Through the Pauline tone of the letter, the cordial exchange between the Pope and his « Very Dear Daughter in Jesus Christ » remains apparent across the years. Human sentiment is elevated to equal the ardour of the first Christian communities who were conscious of living in the Last Days. Current events are taken up into a theology of history which has as its goal, within the existing turmoil, the consummation of all things in Christ. This Biblical perspective allows the Pope to give an interpretation of the misfortunes being suffered by the Church.

We too find ourselves at a loss when politics takes precedence over our religious convictions. Although the separation of Church and State in France has turned former enemies into partners engaging in a constantly renewed dialogue, conflict remains a possibility. Concern with the Last Days has given way to discussion between people of differing opinions in a pluralist democracy. The Gospel does not change. Our society has altered. How can we in our turn, understand the consoling power inherent is Blessed Mary’s life?

It is good to return to the text of the Papal Brief. The reader will be surprised by an omission. Nowhere is there any mention of Blessed Mary’s prayer life. Her virtues relate to devotion to duty and abnegation. Childhood purity, conjugal love, the education of her children, the management of her household, her concern for consecrated life, religious obedience, Teresian humility and patience in suffering have made her a model of perfection. This perfection implies unrelenting fervour. But is it possible to describe such a life of prayer in some way? It is appropriate at this point to speak once more about consolation. Blessed Mary was herself consoled, and consoled others, through an assiduous reading of the Scriptures, which disposed her to live within the rhythm of the Word of God. One last hand-written testimonial throws light on this disposition, for we still have one of the many messages which Mary of the Incarnation scribbled for the encouragement of one or other of her sisters. It was not an innovation in Carmel. Mary of the Incarnation was imitating St. John of the Cross’s practices in spiritual direction. She was a powerful imitator. No less than three testimonies bear witness to the vigour of her action.

Agnes of Jesus (Lyons), for example, in her response to the members of the ecclesiastical tribunal’s questions, explains the essential meaning of this custom :

« She had a great devotion to the Holy Gospels; she always carried them about with her and copied out passages from them, [some examples follow] on slips of paper which she would give to us when we went to see her » (Riti 2236, f° 3 v).

Her response was motivated by the judges’ questions. They had in front of them a prescribed set of questions, Articles sur lesquels il faut examiner les témoins au sujet de beatification de soeur Marie de l’Incarnation » (« Articles on which the witnesses must be examined with regard to the beatification of Sister Mary of the Incarnation »). The first five articles relate to the life of the Servant of God before her religious consecration. The next four examine her interest in theological matters. Articles 10-17 relate to her life as a Carmelite, what it was possible to say about her humility, her moral virtues, her prayer life, her gift of prophecy, her ascetic practices, her comportment in the face of sickness and death. The last six of the twenty-three articles are questions about her reputation for sanctity, a reputation which developed from the time that her mortal remains were exposed to public view. The Sisters’ responses must be understood in this context; it is only from this that they derive their significance.

When Marguerite of St. Joseph (Langlois) gave an account of Mary of the Incarnation’s attentiveness to Holy Scripture, her testimony related to Article 6, which was concerned with the virtue of faith. In this context, the Carmelite spoke at length about the respect which she showed for the « things of God » – images, devotion to the Blessed Sacrament, the Divine Office … After having mentioned her devotion to relics, she dwells on her familiarity with the written record of the Word of God. It is here that we touch the heart of Christian experience for when Sister Marguerite says that « She had written maxims from the Holy Gospel on several slips of paper » we must take in the full imort of this gesture. Mary of the Incarnation was, in her turn, « the scribe of Scripture ». And she spread the message : « She gave some of them to me and to each of the Sisters who went to see her ». Spreading the word in this way was one of the first fruits of her meditation; the Carmelite immediately makes this clear; « Practically every time that she met someone, these sentiments were on her lips ». Consolation followed naturally. « It did her good to see her speaking about it », Sister Marguerite added, before concluding « [She] often had that book in her hand » (Riti 2235, f° 759 v). This testimony retains all the spontaneity of the twenty-six year-old Carmelite who had been moved by her older Sister’s devotion.

A third member of the community emphasised this same attitude. She was Jeanne of Jesus (Séguier). At thirty-five years of age, she had already become Prioress of the monastery in Gisors. She had previously held the same office in Pontoise. She continued to be aware of the serious intention behind the prescribed use of « maxims », « She tried to ensure that the souls whom she assisted in the conduct of their interior lives were grounded in them. [that is, the Scriptures] ». She remembered what these slips of paper contained. She began by quoting three of them from memory, before producing more texts as evidence, « I still have at the present time some of her slips of paper in her own writing » she added. Something is remembered. There is little need to commit it to paper, and it is good that Soeur Jeanne began by quoting to the investigating officers the maxims which she had received for her own use :

« In addition, she often made use of the verse from Psalm 21. Ego sum vermis et non homo [I am a worm and no man]. She wrote it down and gave it to me… she also gave me that passage from the Gospel where Peter asks Our Lord, how many times can my brother offend me and I forgive him; should it be up to seven times, and the reply which Our Lord gave, up to seventy times seven » (Riti 2235, f° 815).

The content of the slips of paper reminds us of two of the three pillars of Carmelite life according to the author of The Way of Perfection : humility and charity. And Jeanne of Jesus defines the intention behind such maxims. The person whom Madame Louise called « Teresa of France » used the first example quoted above to « lead souls to love and embrace abasement and abjection » and the second « as a basis for her maxims regarding charity and bearing with one’s neighbour » (Riti 2235, f° 815).

Mary of the Incarnation’s attitude to Scripture undoubtedly made her one of the leading exponents of the spiritual life in the tradition of the Reformed Carmelite Order. If one reads the one remaining slip of paper in her own handwriting, another facet of the foundress’s personality is revealed. The person for whom it was intended remains unknown, but this is what it says :

« St. John, C(hapter) 6. Do not work for food that cannot last, but for that which endures to eternal life, which the Son of Man will give you ».

In these words we must listen to the wisdom of the person who wrote them, someone who remained a lay-sister out of conviction. In the case under consideration, the verb « to work » refers to the accomplishment of the most ordinary tasks. « To work » means to be at work without becoming a slave to it. It follows that a religious who devotes herself to labour should not lose sight of the goal of her Baptismal life, which is to embrace the Salvation bestowed by the Son of Man. And in the Fourth Gospel it is stated that this Salvation is « eternal life ». Mary of the Incarnation was able to convey the meaning of this Gospel by becoming a source of spiritual consolation for her Sisters, among whom she wished to be the least.

The depositions of these Sisters reveal the profundity of that source; it is the Word of God, read and meditated upon in the Scriptures, lived out and handed down in writing. This did not happen without a struggle. The serene Carmelite in Pontoise had been the wife of Pierre Acarie, one of the most influential members of the League in Paris. This political movement held the Calvinist heresy in abhorrence and « La Belle Acarie » was herself an ardent Catholic. The division in the Church had distressed her as much as it would distress the Pope in 1791. They resembled each other in their common suffering. In both cases, their suffering became Gospel-centred through their desire to be consolers and their practice of imparting consolation. Their action is a call to us to moderate our impatience. Those who live a Christian life in a secularised society and draw their strength from the Gospels find themselves marginalised; in the long run, if the fervour of their community lessens, they become prey to discouragement. They owe it to themselves, however, to continue to be salt and light for those whom they consider to be their brothers. They have at their disposal however, a storehouse of wisdom in the printed page where the Word of God is written down. Through the Tradition of the Church, they have been given narratives, wise maxims, prayers and so many other kinds of literature. It is their responsibility to open the Book and to apply their intelligence to Scripture :

« When we grasp the meaning of Your Word we are enlightened; understanding is given to the simple » (Ps 118, 130).

The response to this effort is the work of God : consolation is distress, mediated through His Word. Now that they have been consoled and will continue to be, those who were in distress have the responsibility of carrying on the work by sharing the treasure which they have discovered ! Their words will have become the very words of those men and women from whom they thought they themselves were so far removed.

The testimonials of the three Carmelite nuns, quoted above, are extracted from the process of beatification of Mrs Acarie (ASV, Riti 2235 et 2236, proc. ap. Rouen, s. virt. Acarie, 1630-1633).